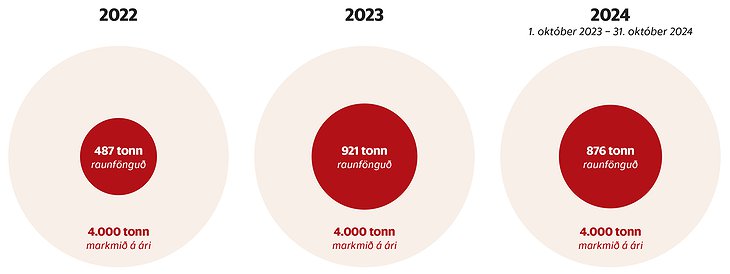

Climeworks in Iceland has only captured just over 2,400 carbon units since it began operations in the country in 2021, out of the twelve thousand units that company officials have repeatedly claimed the company’s machines can capture. This is confirmed by figures from the Finnish company Puro.Earth on the one hand and from the company’s annual accounts on the other. Climeworks has made international news for capturing carbon directly from the atmosphere. For this, the company uses large machines located in Hellisheiði, in South Iceland. They are said to have the capacity to collect four thousand tons of CO2 each year directly from the atmosphere.

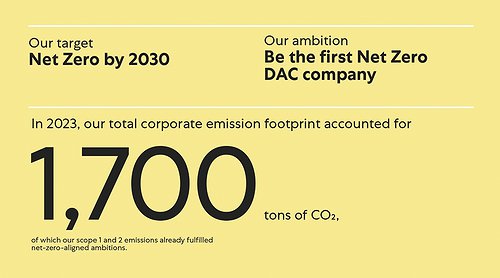

According to data available to Heimildin, it is clear that this goal has never been achieved and that Climeworks does not capture enough carbon units to offset its own operations, emissions amounting to 1,700 tons of CO2 in 2023. The emissions that occur due to Climeworks' activities are therefore more than it captures. Since the company began capturing in Iceland, it has captured a maximum of one thousand tons of CO2 in one year.

The company's operations in Iceland rely entirely on funding from its Swiss parent company, Climeworks AG, but the Icelandic subsidiary's equity position was negative by almost $30 million in 2023. Poor performance in direct CO2 capture has caused a depreciation of the Orca capture machine of $1.4 million in 2023 as the capture plant did not meet expectations, according to the company's annual accounts.

Last year, Climeworks partially commissioned the Mammoth capture plant, which is expected to capture nine times more than what had been done since 2021, or 36,000 tons. That plant has only managed to capture 105 tons of CO2 in its first ten months of operation, according to information from Puro.Earth. It is responsible for verifying the Swiss company's capture and is paid for that work by Climeworks.

Construction on Mammoth began in June 2022, and in a press release about a year ago for the plant's opening, it was reported that 12 of the 72 machines that are to be in the complex had been installed. According to information from Climeworks, work is currently underway to install an additional twelve machines. That work is in the final stages, according to Sara Lind Guðbergsdóttir, Climeworks' managing director in Iceland. According to her, the installation of the Mammoth plant will be completed this year. The Climeworks website had previously claimed that it would be completed last year.

Sara Lind says she cannot answer questions about why CO2 capture is going so poorly that the company is unable to offset its own carbon footprint. She also cannot say when subscribers to the company's carbon credits can expect to receive them.

“You can definitely send me the questions you have, then I can pass them on. Unfortunately, it is not up to me to answer media questions,” she says, offering to mediate in getting Heimildin’s questions to Climeworks in Switzerland. That was two weeks ago, but eleven weeks had passed since the same questions were directed to Climeworks' information representatives in Switzerland. The questions had still not been answered when Heimildin’s print edition went to press on May 8.

A professor of environmental and civil engineering at Stanford University in California says the carbon capture and disposal industry is a scam and is causing harm when it comes to climate solutions. More than 20,000 people pay Climeworks monthly for CO2 capture. A retired scientist in the UK says he feels like a gullible idiot after buying carbon credits from Climeworks, which he hopes to receive in about six years. However, the wait will be much longer unless significant progress is made in capturing carbon quickly. He can therefore expect to receive the two tonnes – which he has already paid for – in a few decades at the earliest.

Optimistic plans

The Swiss founders of Climeworks were ambitious when they started in 2009. In a 2017 interview, they said that by 2025 they planned to capture one percent of all global emissions. That amounts to 400 million tons of CO2. Those plans have not been realised, and the company has never come close to achieving that. They also planned to reduce the cost of capturing each ton of CO2 from the atmosphere to about $100. Today, a ton of CO2 costs about $1,000, according to the Climeworks website – ten times more than the target this year.

Despite not achieving those goals, the company’s executives have set new, more ambitious goals. The company now says it plans to capture 1 billion tons of CO2 by 2050. Climeworks’ operations and ambitious goals have garnered worldwide attention, and the company recently ranked second on Time Magazine’s list of the 100 top green tech companies in the world. This is the first time Climeworks has made the list, but another unrelated company, which has operated in Iceland, made the list last year, Running Tide.

Big machines, little capture

When Climeworks opened its first capture plant in Iceland in September 2021, company officials said it could capture 4,000 tons of CO2 each year it operated. The company sends the carbon dioxide captured by both plants to Carbfix, a subsidiary of Reykjavík Energy, which then pumps it into the ground. Finally, the company sells carbon credits to other companies that emit CO2 and need or want to offset their carbon emissions.

The capture plants work by using large fans to suck air through filters that capture CO2 from the atmosphere. This operation requires a lot of energy, as only a very small portion of the atmosphere contains CO2. The percentage of CO2 in the atmosphere is measured as a percentage of parts per million. According to measurements, there are about 427 parts of CO2 in every million parts of the atmosphere. It should be noted that although this is a small amount of CO2, this small amount has a major impact on the Earth's climate.

In an interview with the Japanese outlet Nikkei, Jan Wurzbacher, CEO and one of the founders of Climeworks, said that for every ton that the Mammoth capture plant captured, up to 5,000 to 6,000 kilowatt-hours of energy would be required. He also said in the same interview that the Mammoth capture plant was not designed with energy efficiency in mind, but only how much CO2 it could capture. This means that for every 1,000 tons of CO2 captured, 5 to 6 million kilowatt-hours of energy would be required. To put Climeworks' energy needs in perspective, it would take up to 72 terawatts to fully offset Iceland's carbon footprint each year, with the country's total emissions of 12.4 million tons of CO2 in 2024. This is equivalent to almost four times Iceland's electricity production, which is about 20 terawatts per year.

Future credits already sold

Climeworks has sold a significant amount of carbon credits. They are not only credits that have already been certified and captured, but also a large amount of credits that Climeworks plans to capture in the future. According to the company, one third of all the credits that the Mammoth capture plant is expected to capture from the atmosphere over the next 25 years have already been sold. About 21 thousand people have a subscription with the company, where they pay monthly for the capture and disposal of carbon credits. The waiting time to receive these carbon credits can be up to six years, according to the company's terms. If Climeworks' capture figures do not improve, the wait could extend from years to decades.

Since the company was founded, it has always focused on capturing CO2 from the atmosphere with capture plants. Now, however, the company has taken a change of direction. Recently, it began to focus on so-called enhanced weathering. This method involves crushing rocks into smaller particles, but this method is controversial within the scientific community. With this method, it is believed that CO2 can be bound to the rock much faster than it already does naturally. The experts that Heimildin has spoken to believe that this step by the company is a sign that Climeworks' capture projects are not delivering the results that were expected and that this method is now being used to try to produce carbon credits that the company has already sold, but is having difficulty delivering.

Failing to offset its own carbon footprint

Climeworks has kept a carbon accounting that the company publishes on its website. It states that it is growing rapidly and now employs 387 people. That is an increase of 45 percent between years. It also says that the company has been expanding systematically and in 2023 it entered new markets, such as the United States, Kenya, Canada, Norway and the United Kingdom. Due to the company's rapid expansion, its carbon footprint has grown in parallel and is attributed to travel and the company's activities.

Climeworks calculates that its own carbon footprint due to the company's activities is 1,079 tons of CO2 in 2022. The following year it increased by 57 percent, or up to 1,700 tons of CO2. Climeworks' total capture figures since its founding are slightly lower overall, at around 2,400 tonnes. This means that Climeworks cannot yet offset its own carbon footprint. Carbon accounting for 2024 is not available, but there have been no reports that the company is cutting back, so the carbon footprint can be expected to be the same as in 2023. Climeworks captured 876 tonnes of carbon dioxide between December 1, 2023 and October 31, 2024, and therefore a shortfall of almost 1,000 tonnes of CO2 could occur for the company’s plans to offset its own operations.

However, the company does not use the units it captures in its own operations, but has sold them to the company's customers, either directly or through a subscription.

Unfavourable accounts

Climeworks' accounts in Iceland were unfavourable in 2023, with the company's equity position negative by 3.6 billion Icelandic krónur at the end of the year. However, its operational capacity is guaranteed as the parent company in Switzerland finances the operations entirely, while the Icelandic company owes the Swiss one almost 5 billion Icelandic krónur. The value of Climeworks' main asset in Iceland – the Orca machine that captures CO2 from the atmosphere – has also declined significantly because the machine has not met expectations in recent years, according to the annual accounts. The depreciation amounts to a total of 2.7 billion in the operating years 2022 and 2023, and will continue should the machine not have more success in the future.

The Swiss company says it has raised or received approval for around eight hundred million dollars, and is therefore worth at least one hundred billion Icelandic krónur. The largest part of the capital comes from the US Department of Energy and is related to the construction of a giant capture plant that is planned in that country in the future. The operations in Iceland are run in three different companies. The Swiss company owns the Icelandic holding company Climeworks Operational, which also submits annual accounts in Iceland, but under that company are the respective limited liability companies, one that includes the Orca machine and the other that was founded around Climeworks' larger capture machine, Mammoth. The annual accounts of the parent company in this country have been delivered to the tax authorities but are under review, as stated in a conversation with the Iceland Revenue and Customs and therefore not accessible at the moment.

Not only investors have financed the operation of Climeworks. Since the company was founded, it has received approval for over one hundred billion krónur in grants from public sources, as stated on the Climeworks website, including from Swiss and American taxpayers. The Swiss handed over $5 million to the company, while the US government has promised the company $625 million.

Gullible idiot?

“I’m 65 years old and retired when I was 60. One of the things I wanted to do in my later years was reduce my carbon footprint,” says Michael de Podesta, who worked for the UK’s National Physical Laboratory for most of his life, where he studied cold fusion, including debunking it. Michael is one of 21,000 subscribers to Climeworks, but after paying his subscription dutifully for about two years, he began to have doubts. Finally, he wrote on his widely read blog and asked a simple question: Am I a gullible idiot?

“I paid £40 [around 7,000 ISK] a month for fifty kilograms of CO2. I was supposed to get around 600 kilograms a year. I paid them right up until October last year and by then I had paid them to dispose of almost 2.2 tonnes of CO2 and got the tonne for around £800 [135 thousand ISK],” says Michael. He says the project seemed promising at first. He saw coverage of the project in the scientific journal Nature, one of the most prestigious in the world. The science was certainly there: CO2 can be sucked out of the atmosphere and Climeworks’ plans were ambitious.

However, Michael quickly noticed that no matter how much he paid, no CO2 had been captured and disposed of in his name. The math didn’t add up when the energy requirements were examined more closely.

“Maybe I should have read the fine print more carefully,” he says, which says the company plans to deliver the carbon credits in less than six years. In addition to its commitments to subscribers, the company has committed to capturing CO2 from the atmosphere for various airlines and investment bank Morgan Stanley – which alone has been promised to capture 40,000 tons from the air. Based on today’s capture rates, which are about 860 tons per year, those credits would be delivered in about half a century. So Michael is moderately optimistic that he will one day receive the two kilograms.

Michael began asking Climeworks tough questions. He asked for better data but received few answers.

Michael says he was aware that scientists had questioned whether capturing CO2 from the atmosphere was a viable way to tackle the climate problem. The biggest concern was the energy consumption of capturing each ton. This requires a huge amount of energy if done at scale, and the capture process also requires a lot of hot water. Iceland is therefore a good option when it comes to powering machines that want to capture CO2 from the atmosphere. But there are few countries in the world with green and cheap energy like Iceland.

“The company sent out information emails every six months,” says Michael, noting that they were rather sparse in content. So he took the opportunity to send an email back asking how the carbon dioxide capture was going. “I started asking quite specific questions about it all,” explains Michael, who says he received vague answers from the company’s information representatives when he finally received an answer.

“Then the idea came to me; could this be a scam?” says Michael.

So he took to social media X where he asked directly: Is Climeworks a scam? To his surprise, the company's information officer responded much more quickly than when he sent them emails. The company responded badly, he says, and he was criticised for thinking such a thing. Subsequently, however, he found information about the real figures on how much the company has captured.

Michael did not let the criticism deter him, but wrote a blog post with the title: Am I a Gullible idiot? In it, he emphasised that the question of whether Climeworks was a scam was not unfair.

“This has all the hallmarks of a scam. There are undoubtedly a lot of highly paid people traveling the world to sell their services to large corporations to remove carbon credits in the future. They are using a semi-magical technology that doesn't work as well as expected (better known as Orca) but will work perfectly in a larger version (Mammoth). I am urged to convince my friends to join the project. The answers are scarce and full of PR chatter. Climeworks' operations look like a scam and talk like one. But is it a scam? I don't know. I think it could work, but the company's answers are so opaque that it's hard to say.”

Michael says his biggest question is simple. “Why are they scaling up so slowly? There’s nothing special about the factories themselves. They’re not even that complicated,” adds Michael, who has dedicated his life to science. The answer is probably that the energy demand is enormous.

He says he can’t answer yet whether he’s a gullible man. Climeworks has until 2027 to deliver the product he paid for, which is to capture and dispose of 2.2 tons of CO2. “But I definitely feel that way, like I’m a gullible idiot,” he concludes.

Carbon capture “the Theranos of the energy industry”

A professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University in the United States, Mark Z. Jacobson, says the capture and disposal industry – abbreviated CCS in English – is nothing more than a scam. “This is the Theranos of the energy industry,” he says in an interview with Heimildin, referring to the notorious fraud company of Elisabeth Holmes, who claimed to be able to diagnose diseases from a single drop of blood with a machine that never worked. The analogy is clear, even if it is presented here symbolically. Mark intends to say that the carbon capture industry is nothing but a scam.

“Direct capture is a scam, carbon capture is a scam, blue hydrogen is a scam, and electrofuel is a scam. These are all scam technologies that do nothing for the climate or air pollution,” Mark says bluntly.

Mark is well known in his field in the United States and was, among other things, an expert witness in the first climate trial in the United States, where the plaintiffs are sixteen children. They demand that their right to access clean air and a healthy environment be recognised. Mark himself has been repeatedly called upon as an expert on environmental protection issues in the American media. In 2009, he published a scientific article in which he said that the most successful path for the world was to switch entirely to renewable energy, such as solar, wind and electricity. As a result, he has been criticised, including by his colleagues.

Mark is adamant that carbon capture and storage are designed to delay the energy transition. “This technology perpetuates the business model of oil and gas companies,” he says, adding: “This is what this technology is designed to do. None of this is doing any good for the climate. On the contrary, this kind of technology is making things worse.”

Mark conducted a study on the impact of CCS technology and published it in 2019. “We looked at what would happen if 149 countries adopted CCS technology and compared it to renewable energy. If we used only renewable energy, we would eliminate about 90 percent of global air pollution, with the added benefit that 7.5 million people would not die from air pollution. Carbon capture would not prevent any of these deaths; on the contrary, the technology would add a million lives to the problem per year if the energy used to power industry were not renewable. If it were renewable, nothing would change, seven and a half million would still die annually, and green energy would be wasted on this technology,” Mark explains, asking: “Why would you waste green energy on this instead of replacing fossil fuels?”

He says the conclusion is simple. “By powering this technology with green energy, the CCS industry is adding to the number of deaths each year from pollution, by preventing renewable energy from replacing fossil fuels.”

No benefits

Mark also points out that the energy requirements of this technology, especially direct capture, are enormous. This has its effects. “If this technology is used, the demand for green energy increases, which in turn increases its price. So pollution increases, as does demand and thus the price of renewable energy. That cost is ultimately passed on to consumers, who are also left with the same air pollution, if not higher in the future,” says Mark, adding: “There are no benefits to this technology. It is just harmful.”

He says Climeworks uses traditional methods to embellish its numbers.

“This is a typical embellishment of the real numbers that these types of systems manage to capture. The big picture is rarely considered when carbon dioxide is captured in this way,” says Mark.

“The energy production to power this increases emissions, and no matter how you look at it, they are increasing emissions by not using it to replace fossil fuels,” he adds.

He says he understands that projects of this nature may look like a solution to the climate problem. However, that is not the case. “I’ve been working on this and researching it for decades and I understand it incredibly well for those reasons. But 99 percent of people don’t get this complex interaction and instead grab what they hear on the news or read online. And most of what’s out there is positive. It was initially pushed on the public and the government by oil and gas companies. Then it took on a life of its own. People want to make a difference, they want to do good, and they want to tackle the climate problem. Without understanding the context, these ideas might seem like real solutions. But they aren’t,” says Mark, adding that once people get involved in an industry like this, it’s not easy to turn their backs on it. “Because that’s where the paycheck comes from,” he concludes.

Athugasemdir (1)